Exhibitions: Nina Howell Starr

Nina Howell Starr

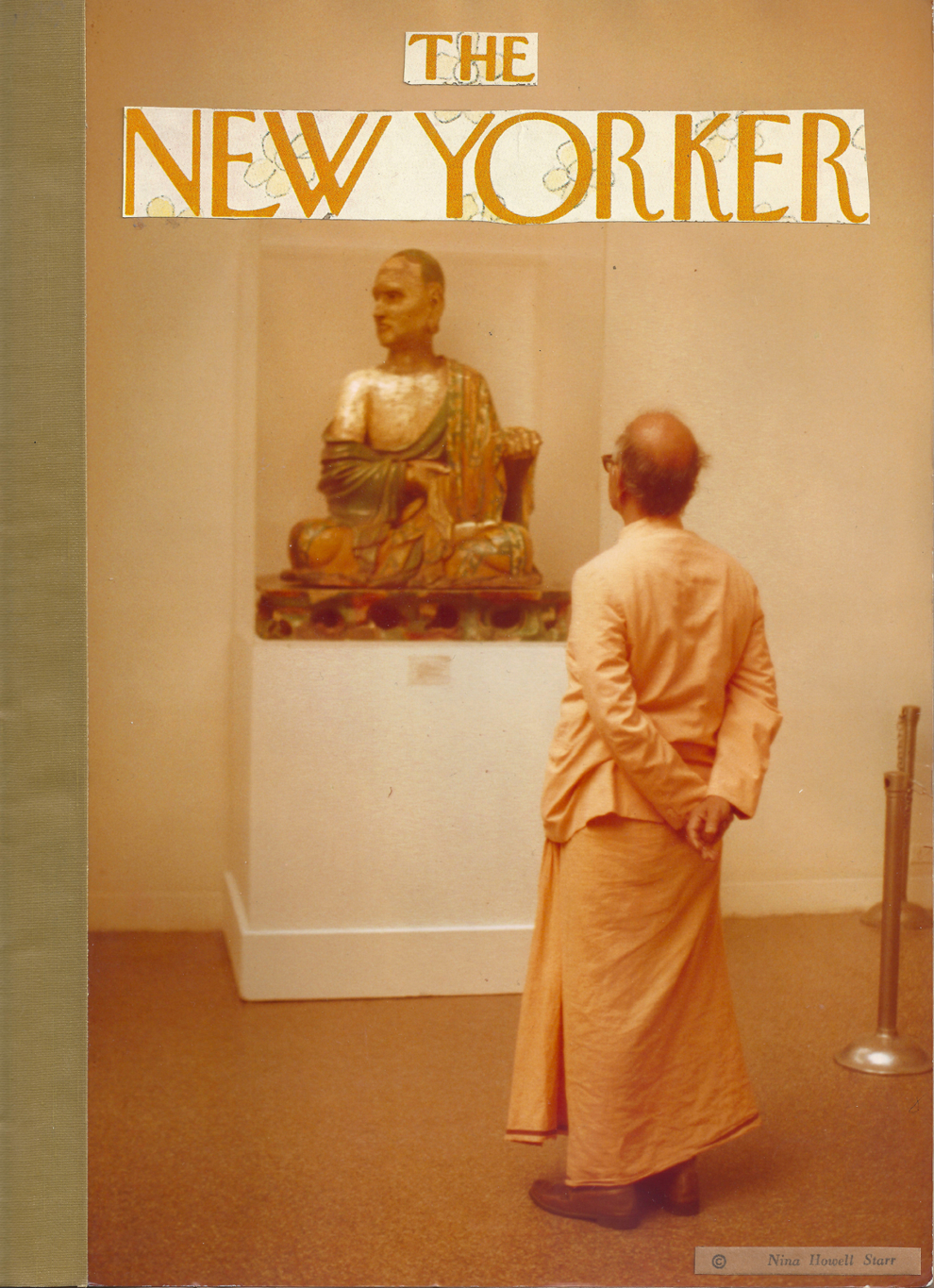

The New Yorker Project

November 5 - December 12, 2015

Nina Howell Starr

The New Yorker Project

November 5 – December 12, 2015

Institute 193, Lexington

Nina Howell Starr (1903–2000) was a lifelong advocate on many subjects, with strong opinions on all. These included but were not limited to: modern design, racial equality, good manners, the English language, folk art, women’s rights, photography. Numerous were her letters over the years to editors of art, design, and photography magazines—and her daily reading, The New York Times. Whatever the subject, she was always involved and opinionated.

Especially numerous and incisive were Starr‘s opinions on her chosen artistic medium of photography, and she did not suffer fools gladly. When she was guest-curating an exhibition of painter Minnie Evans at the Whitney Museum of American Art, for example, and its then-director, Thomas Armstrong, complained that her photograph of Evans was “blurry,” she replied, indignantly, “Focus is part of the language of photography!”

Starr’s quixotic mission to convert The New Yorker magazine to the use of photography stemmed from her awareness of the magazine’s strong graphic traditions. She had long noticed that in addition to the well-known cartoons, each issue of the magazine included dozens of tiny “filler” drawings in black and white. Their size made it imperative that they incorporate strong graphic concision and often an element of visual wit—two primary concerns and characteristics of her own photographs. Starr had been a follower of The New Yorker since it started in 1925, and, fifty years later, she undoubtedly felt that in continuing to neglect the illustrative possibilities of photography into the late 20th century, The New Yorker was for once falling badly behind the times.

In September 1979, to prove to The New Yorker that photography could equal if not surpass the effectiveness of drawing, Starr decided she would simply take an existing issue and replace every editorial drawing—except for the cartoons but including the cover—with one of her own photographs and mail the resulting maquette to the art editor. She also made a separate portfolio of all the photographs, printed to size and mounted on card stock.

The results—which the magazine sent back to Starr with the knee-jerk response “we do not use photography”—are shown in this exhibition, and tell their own story. Of course, Starr got the last laugh. The New Yorker printed its first photographic illustrations (uncredited) in 1987. In December 1992, thirteen years after the dismissive scrawl to Starr, the magazine announced with some fanfare the appointment of its first “Staff Photographer,” Richard Avedon.

This exhibition is presented in conjunction with University of Kentucky Arts in Healthcare. A companion exhibition of Nina Howell Starr’s work, An Empathetic Eye, is on view at the UK Albert B. Chandler Hospital now until March 2016.

Nina Howell Starr got a late start as a serious photographer at the age of 53. Born in the same year as Aaron Siskind, Walker Evans and Russell Lee, she stands photographically and professionally outside her own generation, and made much of her best work in her 70s, in New York City, where her colleagues were mostly much younger. Though she was for the most part not an innovator, her vision was fresh and personal, and the work a deeply felt response to genuine necessity, combining compassion, wit, and strong sense of abstraction and design.

Nina Howell Starr was born Cornelia Margaret Howell in Newark, New Jersey in 1903. She attended Wellesley College and graduated from Barnard in 1926. In the summer of that year she married Nathan Comfort Starr, an English professor, and they settled initially in Cambridge, Massachusetts, later moving to Williamstown, Massachusetts, Annapolis, Maryland, then Winter Park and Gainesville, Florida, according to the vicissitudes of Nathan Starr’s academic career.

From the beginning of her married life, Starr was an informed and passionate follower of modern art and design, and an indefatigable letter-to-the-editor writer and gallery-goer. She took graduate courses in architecture in the mid-’30s at the newly founded Bennington College. Starr was for many years the unpaid representative and tireless advocate of the outsider artist Minnie Evans, whom she met in 1962 and whose works she introduced to galleries and other exhibition spaces in New York, including the Whitney Museum, where she guest-curated Evans’s solo exhibition in 1975. While living in Gainesville in the ‘50s and early-‘60s she became deeply involved in the interrelated issues of housing policy and race relations. All of these different interests very much informed the photographic work that she began seriously in the 1950s when she enrolled as a graduate student at the University of Florida at Gainesville (where her husband was teaching). Starr earned her MFA in photography in 1963 at the age of 60, studying with Van Deren Coke and Jerry Uelsmann.

Upon Nathan Starr’s retirement from the University of Florida in 1964, the couple moved to New York City, where Nina quickly became involved in the photographic, artistic and feminist communities. She was a member of New York Professional Women Photographers, 20/20 New York Women Photographers, and The Photographic Historical Society. She exhibited in many group and solo shows. Though she stopped taking photographs in 1985, she continued to participate actively in the art world well into her 90s, attending galleries, exhibiting and publishing her photographs, as well as writing articles, statements and disputatious letters. Starr died in 2000 at the age of 97.

—Nathan Kernan

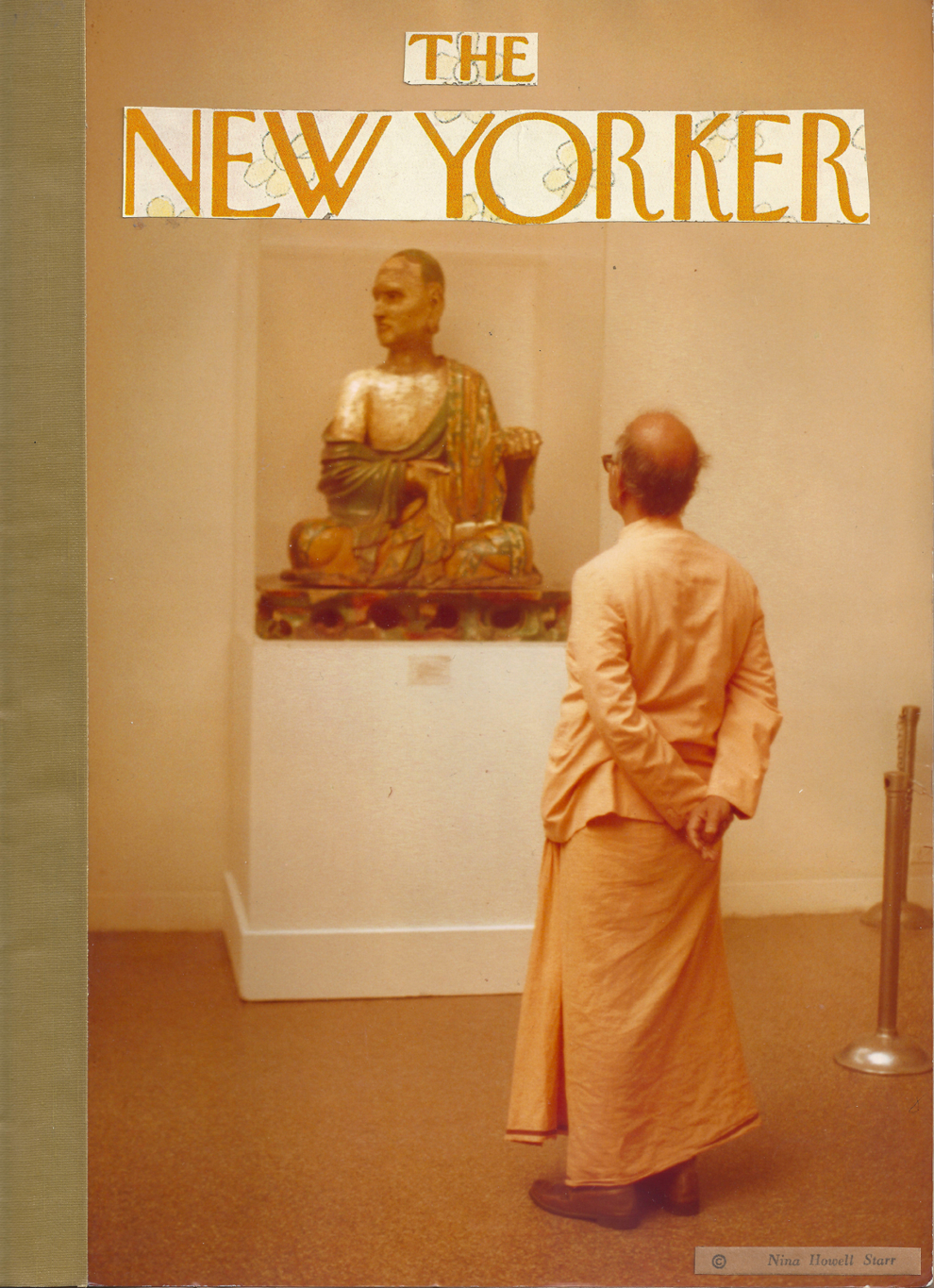

Nina Howell Starr, Untitled (#43, p. 97), c. 1970s, photograph on cardstock, 7.75 x 9.75 inches

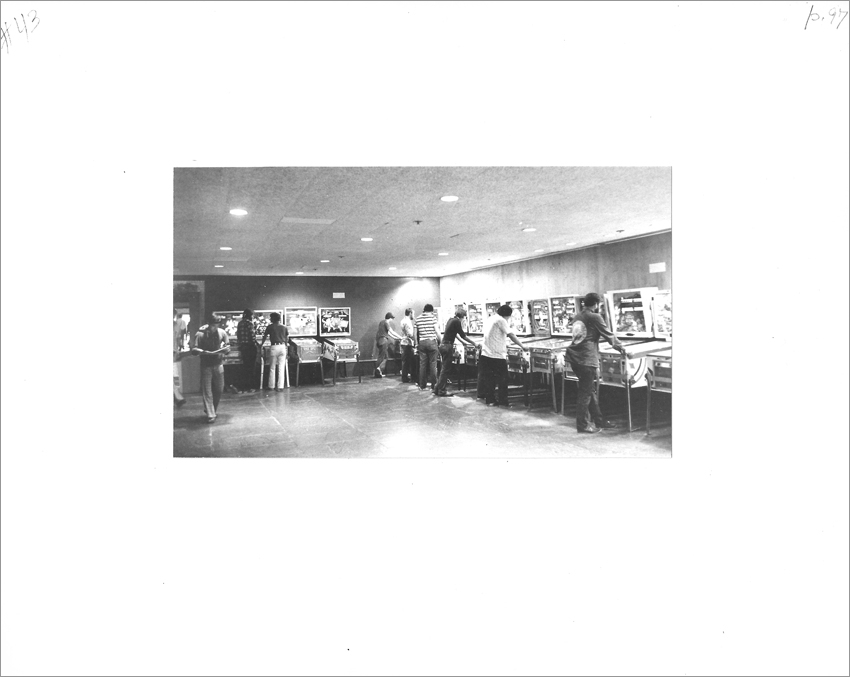

Nina Howell Starr, Untitled (#31, p. 76), c. 1970s, photograph on cardstock, 7.75 x 9.75 inches

Nina Howell Starr, Untitled (#18, p. 46), c. 1970s, photograph on cardstock, 7.75 x 9.75 inches

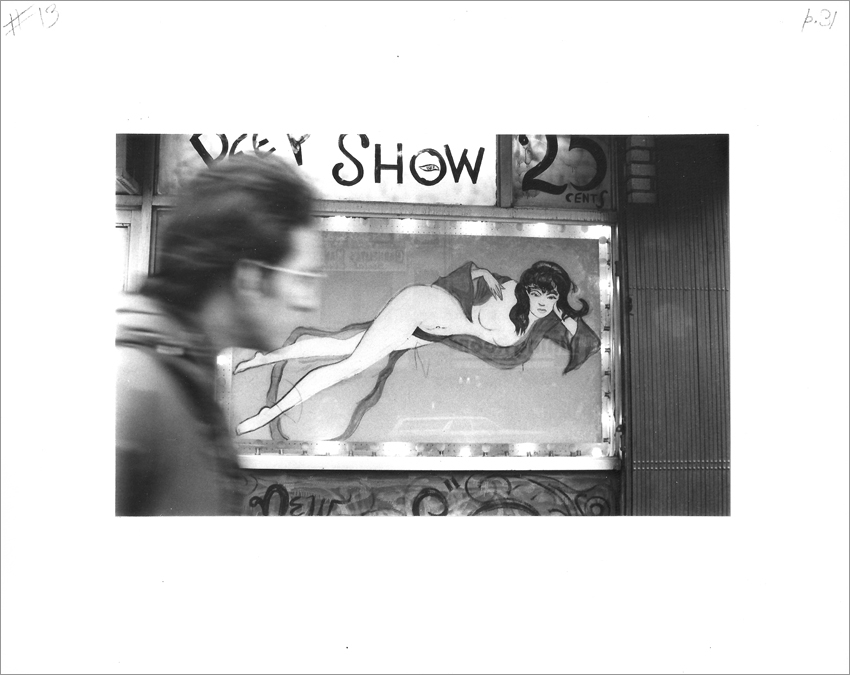

Nina Howell Starr, Untitled (#13, p. 31), c. 1970s, photograph on cardstock, 7.75 x 9.75 inches

Nina Howell Starr, Untitled (#1, p. 4), c. 1970s, photograph on cardstock, 7.75 x 9.75 inches

Nina Howell Starr, Untitled (#5, p. 12), c. 1970s, photograph on cardstock, 7.75 x 9.75 inches

Installation View

Installation View